Following an invited competition, Eric Parry Architects were appointed to The Holburne Museum, and asked to compile and submit a Stage One Heritage Lottery Fund Application for the refurbishment of the museum itself. The proposal included the new extension onto Sydney Gardens that offers café at ground level, as well as new gallery spaces on the upper floors, and a new archive research facility, ensuring the future of The Holburne Collection. With a strong base of local support in Bath, the proposal had as its main aim to enhance the historic building itself and its relationship to the collection and the surrounding park. Servicing solutions, the sourcing of materials and the methods of construction were considered in relation to their environmental impact throughout all stages of design.

View of the Holburne Museum main façade from Great Pulteney Street.

To reconnect the town to the garden, it was necessary to reposition Blomfield’s stair and reuse the inadequate lift, which meant removing the internal elements of the three-storied rear volume.

Detail of the corner.

The structural response by Richard Heath, of Momentum, was to create stiff floor plates that step outwards. The first floor plate is propped by the cruciform posts (designed to reduce transversal impact). The walls of the double-height chamfer above are designed to prop the floor slab of the top lit gallery above, the central section of which is held by four diagonal corner struts. The whole is given rotational stiffness by the concrete wall that supports the lift well. The permanent display, first floor and mezzanine of the new extension, setbacks, double-height openings and light well, all contribute to the spaciousness of the interior.

Descending through the opening between the double-floored space of the gallery containing the permanent exhibition, collection pieces of porcelain can be viewed from multiple angles. Below, an assortment of the original collection is carefully displayed in line with the taste and aesthetic criteria prevalent in the original collection, bringing together original antique pieces of painting, furniture and china as well as tasteful eighteenth-century forgeries that were then en vogue. The intimacy of the space calls on the detailed attention and curiosity of the visitor. The depth of the space is punctuated on both levels by the double-height opening to Sydney Gardens.

On the upper floor of the new building there is another new gallery space for temporary exhibitions. The adaptability and changing nature of the gallery space is accentuated by the difference in light from above – here the darker concentration on individual sculptural pieces in the exhibition ‘Presence: The Art of Portrait Sculpture’ (May-September 2012), curated by Alexander Sturgis.

The adaptability and changing nature of the gallery space is further accentuated by the difference in light from above – here the brightness of the temporary exhibition ‘Peter Blake: A Museum for Myself’ (May-September 2011).

Blomfield’s fine purpose designed top lit gallery was plagued by compromises; air quality, lighting and an array of radiators that make hanging very difficult. The largest Gainsborough pictures needed to be deframed to take them out of the gallery. Close controlled environmental air conditioning has been carefully integrated into the original ceiling plaster work, the main doors glazed and widened and the whole reserviced, relined and redecorated.

View of the first floor ballroom. Metaphor’s dining ware display forms the single central display, replacing a turgid set of older cases; cabinets of ceramic and silverware form the wall displays with pedestals for some of the finest intimate sculptures in the collection.

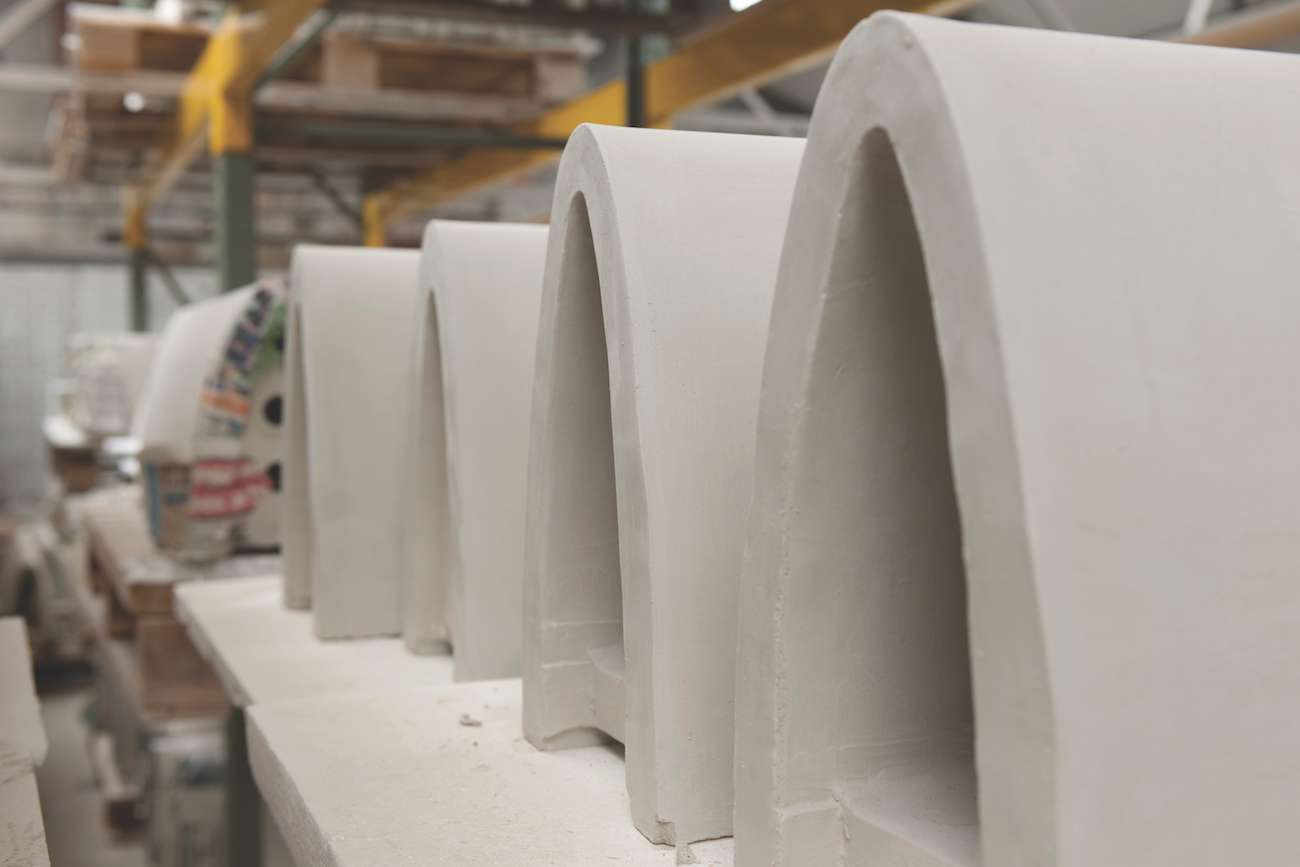

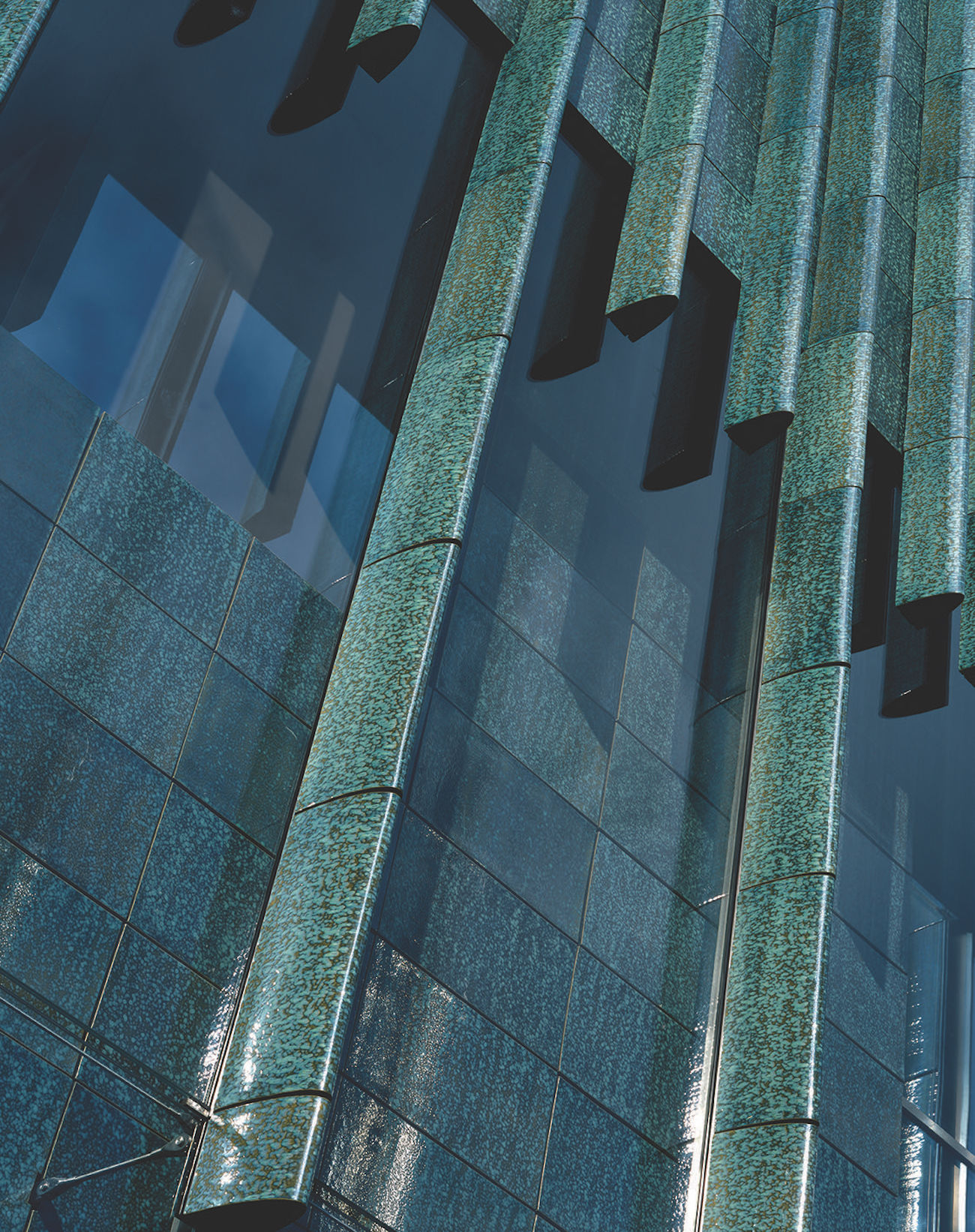

The careful and detailed attention placed on the design and manufacture of the external fins is perhaps best reflected in this sequence of images, showing the primary role of handcraft in producing each element of the façade, alongside the most advanced ceramic technology available.

The ceramic revetement on superimposed glass applied to the façade ensure optimal thermal stability. The careful chromatic balance of the ceramics, the transparency and reflection of glass, mirror the tree landscape of Sydney Gardens as a continuous dialogue of transparency and reflection, of building and landscape.

Interstitial space of one of the lobbies linking the old building (now restored) to the new gallery exhibition spaces. From above, natural light pierces through the space marking the transition and resolving the different transpositions, from stone to metal and painted stuccoed walls, with the change in flooring demarcating the difference.

The original stone arch where each stone is cut utilising a classical tradition of stereotomy. The arch leans on the bespoke metal structure reminiscent of the early use of metal in the Romantic Classicism of late eighteenth- and early nineteenth-century architecture, a reference to the so-called ‘serliana’ or Palladian arch motif, appearing also on the pre-existing Sydney Gardens elevation.

Autumnal view of the new building mirroring the colours, textures and qualities of the Sydney Gardens landscape. The visual texture of ceramic fins of the outside shell of the building reflects the quality of much of the ceramic and porcelain within.